Michael James, and Judith James

-

Bio

I was primary caregiver for my wife Judith from her diagnosis of younger onset Alzheimer's disease in 2009, to her death in August 2015. During that time, and currently, I served as a tenured professor at a Research 1 university in the midwest, and my wife had taught as a visiting lecturer in my department until just before her diagnosis. We have one adult son and two granddaughters who live on the east coast. We're both originally from southeastern New England, where we lived for the first fifty years of our lives. We met in undergraduate school and were married for 43 years. Many ironies materialized around this situation over the years, her going into hospice care on our 43rd wedding anniversary being one of them. We never reached the 50 year benchmark we had both looked forward to.

Website URL

-

Which of these best describes you?

I am a caregiver - With no family closer than 1500 miles, and most of our social circle comprised of fully employed professionals, it was a big challenge to manage my wife's increasing care needs as her disease progressed. Professional care providers from Home Instead made it possible for her to remain at home through the middle stages. In January of 2015 she began going to day services at a memory care facility, and shy of three months later she became a full time resident at this same facility. This transition went smoothly, for which I'm grateful. I continued to have her original paid care providers visit her weekly, on a rotating basis, so that she was able to continue those relationships as long as possible. She really bonded well with five women in particular, all of whom I think of as her angels. Her decline accelerated in the last few months, as that late stage progressed. Nonetheless, she enjoyed life and was lucky to be in a situation where everyone was loving and supportive.

-

If your loved one was experiencing signs of dementia, would you keep it a secret?

No - We talked this through initially, just after we received her diagnosis. Judith didn't want anyone to know at first, and resisted sharing it. I argued that keeping it secret would work only in the short term, and that it was nothing to hide in any case. It was something we were going to have to live with, and our friends and family needed to be a part of that so that they could learn as we would learn. I don't think that she managed to get past the embarrassment she felt in admitting to her diagnosis until she reached the point at which she no longer recognized that she even has a disease. So I guess I'd say that the disease itself eventually takes care of the denial, at least for the sufferer. It even has a clinical term, anasognosia. Since I've never felt that it was something to be embarrassed about, I tried to inform people, as others' understanding has always been helpful. Yes, our society still stigmatizes dementia type diseases, but I think that education is the key to erasing the stigma. Nearly all of us will know someone or care for someone who has a disease that leads to dementia. Knowledge is power, and it's also the root of empathy.

-

Who are you here for?

Partner - The diagnosis really set us adrift, and we both felt completely unmoored, rudderless, at sea with no map and no sense of which direction to head in. For me it was a concentrated process of learning as much as I could about the disease, and for Judith it was a long and gradual process of coming to accept her diagnosis and the losses that mark the progression of the disease. I know that we were both helped by the depth of our love for one another and the more than four decades that we've been each other's partner and soul mate. Alzheimer's only deepened that love and our relationship.

-

The thing I miss most is...

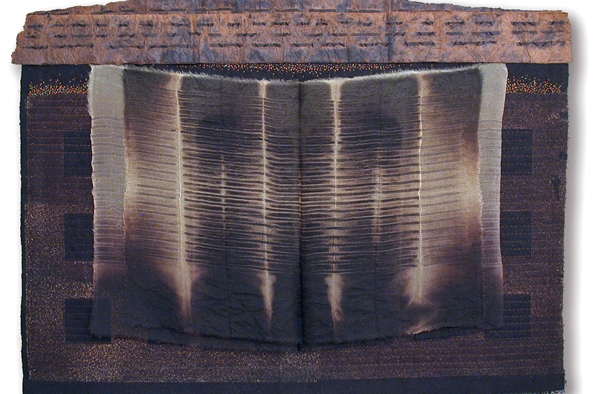

- My wife was an artist, as I am. We met in art school, and our mutual interests in all of the arts scaffolded many decades of travel, museum and theater-going, shared reading, and so on. After spending about 25 years in the home sewing industry (she taught sewing and tailoring and owned a retail fabric and sewing machine business) Judith went back to school when we moved to the midwest, and completed a Master of Arts degree in textile design. She began a successful studio practice that led to both national and international recognition and solo shows in France, the UK, Switzerland, and South Korea. It was, alas, short-lived. By 2010 she could no longer work through the complex technical and conceptual processes that her work developed from. I missed her working in her studio, when she seemed so focused, empowered and content.

-

I first began to worry when...

- There were indications that something wasn't quite right as far back as 2007, two years before her diagnosis. I had had no experience with Alzheimer's and didn't know how to read the signals I was getting. My instincts told me to take our financial advisor up on her offer to get us set up with long term care insurance. Judith was denied coverage, and that sent us to a neurologist, and then to a second one, who confirmed the diagnosis.

-

The hardest part of my today was...

- That was always complicated. It was something like survivor's guilt I guess. Maybe the hardest part of every day was knowing that she could no longer do all of the things that she loved to do, and that we both took for granted. Hop in her car and run over to the gym for a yoga class. Prepare a nice meal to enjoy outdoors on a summer evening. Meet with her book group to talk about that month's reading. The list goes on. I, on the other hand, still got up and went to work, enjoyed the challenges of leading a department at a flagship university, engaging with colleagues and students, and continuing my own creative work in my campus studio. But I looked forward to visiting her every evening, talking about some of the things that took place each day, walking around the memory care facility and sometimes chatting with other residents, having some ice cream, sitting in the garden to watch the moon rise. I helped her change into her sleepwear and helped toilet her, then I tucked her in and promised to be back the next day. So, maybe leaving her at that point was the hardest part of each day, at that late stage in her disease. Our bed felt pretty empty once she was no longer in it.

-

The best part of my day today was...

- I think the best part of each day was the moment when I showed up at memory care and my wife lit up when she saw me. She still knew who I was and other visitors told me that she talked about me and about our granddaughters when I wasn't there. Once I rejoined her, everything else seemed unimportant. We settled into the moment, I held her hand and that reassured both of us. We still had that measure of intimacy. Touch is so important to human communication and centering. I noticed how the staff at memory care used touch to calm, to reassure, to affirm. For people who are past words, it's especially critical.

-

I didn't consider myself a caregiver until I had to...

- There was no single moment when that realization set in. It was more cumulative than sudden, an awareness that we'd arrived at a point at which her safety and security depended on my oversight. Each loss was gradual - cooking, for example: something slightly under- or over-cooked, then an ingredient left out, then the process set aside mid-preparation and forgotten. From that point I knew I would be preparing and serving our meals. The losses accrue, and then one day you realize that caregiving is what you do. When my son was a child, I worked from home and was able to share all of his caregiving with my wife. So I'd already seen myself in a caregiving role, in a sense. The caregiving a parent provides lessens as the child grows, and with Alzheimer's, it's exactly the reverse. Caregiving demands only increase as the illness worsens.

-

I have found the most support from...

- Support came from all sorts of directions, from paid professionals with rock solid experience and expertise, to fellow travelers on the same journey - especially a small group of husbands of early onset wives that I've been fortunate to know - to concerned colleagues, to old friends and newer friends far and wide who stayed in touch, sent words of encouragement or who came to visit and, in a small way, provide care themselves. Once Judith was in memory care as a resident, her facility's staff proved enormously supportive to me. They lived and worked with this reality and saw it in all of its diverse expressions. They formed bonds not only with their residents but with their residents' families. I saw how hard it can be for the professional staff. Alzheimer's is a terminal illness and death is part of the ongoing cycle in a care facility. This takes a toll on the staff people who cared for these residents, just as it does on the families and friends. I could see that they needed support too. It's a challenging job and they do it with dedication and enormous caring.

-

I have felt most abandoned by...

- Interestingly, the pleasure I always took in artmaking seemed to abandon me when we we got the diagnosis. No matter what was going on in my life, I'd always been able to go into the studio and be re-directed, re-focused, sometimes transformed by my work there. Once we had her diagnosis, inspiration evaporated, and the studio seemed to give me back very little. I no longer felt any energy there, as I always had – it was as if the air had been sucked out of the space. It took several years for that fresh air of inspiration to return. Though I felt in some ways abandoned, I never abandoned the studio nor the work. I kept at it, with much effort, because if I've learned anything over the course of a lifetime of artmaking, you have to keep doing the work, regardless. Eventually ideas began to flow again, circulating around our circumstances and what it all meant. I think it helped me produce some of my best work to that point, so in some ways I have the disease to thank for that. When life gives you lemons, make lemonade. I mounted a solo exhibition in a museum just a few months before Judy's death, and I thought it did a good job of capturing the territory of ambiguous loss and grief.

-

The thing that would surprise most people about my day is...

- I don't think there was anything that was very surprising about most of my days. I got up and took the morning paper from the front step, I showered and dressed and had breakfast, I paid a bill or two or returned a call, then headed to my office. I worked – meetings, e-mail, letters to write and sign, students and faculty to advise, projects to advance. I ran an errand or two on my way home, I ate some kind of dinner for one – sometimes whatever the refrigerator held, sometimes a 'real meal' when I had time to actually cook – I had a glass of wine, watched a bit of news, then I headed to my wife's memory care residence, to spend an hour or two with her. Some evenings we sat in the activities room with other residents, talked with staff, walked to her room, changed her into sleepwear, watched a little bit of Antiques Roadshow which she had always enjoyed. I'd tuck her in and kiss her goodnight and then head home. She slept pretty well there most nights I'm told, and for the first time in years I found that I was sleeping through the night more often than not. Sleep is so important to health, and I knew that sleep deprivation was had a big impact on how I got through each day, and how I felt during those years. So that knowledge impacted my decision to place her when the opportunity came. It wouldn't have helped for me to get sick too.

-

The funniest thing that has happened was...

- The residents of Judith's memory care facility could be very funny, and their matter-of-factness was often totally disarming. One evening we were in the activities room and the residents were playing a word game with the staff assistant. I started chatting about something with one of the residents, whom I'll call Liana. In the middle of explaining something to her, that staff assistant interrupted me with a question and I chatted with her for a few minutes. When I turned back to Liana, I couldn't recall the point I was about to make and she tried to help. "You were talking about the box" she offered. "Hmmm, Liana," I replied, "I can't for the life of me remember what I was about to tell you." Straightfaced she looked up at me from her wheelchair and said "Well, you're in the right place." Several other residents chuckled along with me. That was right on target. To this day I can't recall what I had been about to tell her.

-

The gift of being a caregiver is...

- ...learning that loving deeply, and being loved deeply, can find expression in very unexpected ways and in unexpected conditions. In some ways, looking back on forty-three years of married life, it was all a dress rehearsal for the last years, months, weeks, hours. It was a difficult but valuable education.